Most new migrants to Sweden have heard the horror stories of the housing queues. In Stockholm, the average waiting time for an apartment is nine years. So can anybody new to Sweden really expect secure housing before the heat-death of the universe?

Yes they can. I moved into an apartment in a major city with a first-hand contract after just one month in the country. How did I do this?

Contract types

Sweden has a rental system that may seem peculiar to newcomers. Swedish law offers strong tenant protections relative to the two other countries I’ve lived in, the UK and the USA, although the exact level of security depends on the type of contract you have.

First-hand contract (första hand)

This is the gold-standard situation for a renter to find themselves in. With a first-hand contract you are renting your apartment directly from your landlord. These are great because the rent is typically controlled, meaning the annual rent increase is capped by law. And, crucially, once you have a first-hand contract you have a tenancy for life. There is no fixed term and no chance of a no-fault eviction; you decide when the tenancy ends by giving three months’ notice.

First-hand contracts are often (but not always) awarded via a queue system, giving priority to those who have been waiting the longest for an apartment.

(A quick note on landlords. Unlike the UK, where buy-to-lets have fuelled a rental system dominated by small amateur landlords, Swedish apartment buildings tend to be owned and managed by much larger organisations. Mine is owned by Länsförsäkringar, a customer-owned insurance company. This brings a large degree of uniformity to the tenant experience.)

Second-hand contract (andra hand)

A second-hand contract is what is called subletting in the UK. Instead of renting directly from the landlord, you are instead renting off their tenant.

Sweden has strict rules around subletting. The good news is that the first-hand tenant doesn’t have free-rein over the amount of rent they charge you. However, these arrangements are strictly time-limited: typically for 6-12 months and very rarely more than two years. The rationale for this is that the first-hand tenant should give up their contract if they can’t live there, allowing somebody else to take it on fairly.

Because of the long queues for first-hand contracts, second-hand renting is generally the fastest way for a newcomer to find a (temporary) home. One advantage of a second-hand apartment is that they are often furnished (albeit with a rent premium of up to 15%), which is not the case with first-hand rentals.

I went straight from a hotel into a first-hand apartment, so I have no experience to share regarding second-hand contracts.

The housing queue

This is a bit of a misnomer, as there is not one single housing queue, but many. Each city has a queue, as well as some landlords and other agencies maintaining their own queues outside the municipal systems. My only experience is with Boplats Syd (literally ‘Residence South’), which is the municipal housing queue for Malmö and the surrounding Skåne area.

The great thing about Boplats Syd is that I was able to join their queue before I was even in Sweden. I paid a 300 kr (about £24 / $32) annual fee back in February, as soon as I had been approved for Swedish residency, but before I even knew that Malmö was to be my destination.

The system is simple enough. You get one point for every day you are in the queue, and when you apply for a property you will be ranked against other applicants based on how many points you have. When you find somewhere to live, your points reset to zero.

In the days before my move in August, I browsed Boplats Syd’s map of Malmö, getting a sense of the queue lengths in each area. The website helpfully told me where in the queue I would be for each property, as well as how long the person at the head of the queue had been waiting for an apartment.

In the more popular areas of Malmö, there could be dozens of people in the queue for each property and I would slot in somewhere near the back, giving me a practically zero chance of being allocated the apartment. Those at the head of the line can often have many years of queuing.

Take this apartment in the popular Västra Hamnen (Western Harbour) area of Malmö (near the Turning Torso). At the time of writing, it has 42 applicants, with the #1 slot occupied by somebody who joined the queue in 2011. A newcomer to Malmö is not getting that apartment.

But don’t lose heart. There are a few pleasant areas of Malmö, typically new areas with lots of recent residential construction, where the housing queues are much shorter. The area I zoomed in on was Limhamn Sjöstad, on the western edge of Malmö (technically in the distinct town of Limhamn), occupying the coastline between the Øresund Bridge and Ribersborg Park.

It is a quiet, safe area with good local facilities, including shops, cafes, bars, parks, the sea and good public transport. But it’s also a little further out from central Malmö than other areas and has a lot of new-build accommodation. This makes the housing queues much shorter.

Getting a first-hand contract within 11 days

A few days before moving to Sweden, I expressed an interest in one apartment for which I was ranked second by queue points (annoyingly, the person ahead of me had only joined the queue a few days before I had). To my surprise, when the application period ended I was offered the contract, as the person ahead had dropped out.

I had been in Sweden for just five days and was living in an aparthotel on the other side of the city. I was very excited to have got a first-hand apartment in the bag so quickly.

Not so fast.

Almost immediately, my excitement began to unravel, as Boplats Syd required evidence of the salary I draw from my company, taking into account only the smallest amount I had paid myself in the preceding three months. At this point, I was still technically employed by my school in the UK for another few weeks, so there had been no need to pay myself a large salary each month, meaning I didn’t meet the income requirements for the apartment.

I walked into the city centre to argue my case in person. They were sympathetic, as they could clearly see that I could afford the apartment, but computer said “No”.

After a few days of back-and-forth, I received a final no from Boplats Syd. The apartment would not be mine. We discussed how long I would have to wait to prove my income in Sweden and I asked if it would be a problem that this income will initially be in the form of dividends. He said he would look into it and let me know.

The next day, moments before I was about to extend my hotel stay for another month, Boplats Syd called me back. The calculation is different for dividends. Instead of being based on the minimum salary over three months, it is based on the average dividend over 12 months. Before I left the UK, I paid a large dividend to allow me to buy a car in Sweden. This, averaged over 12 months, plus my smaller monthly dividends, tipped me over the edge and made me eligible for the apartment after all.

11 days after moving to Sweden, I had signed a first-hand tenancy agreement. For a relatively low rent (by British standards), I had a one-bedroom apartment with water, heating, hot water, broadband and TV included.

Sight unseen

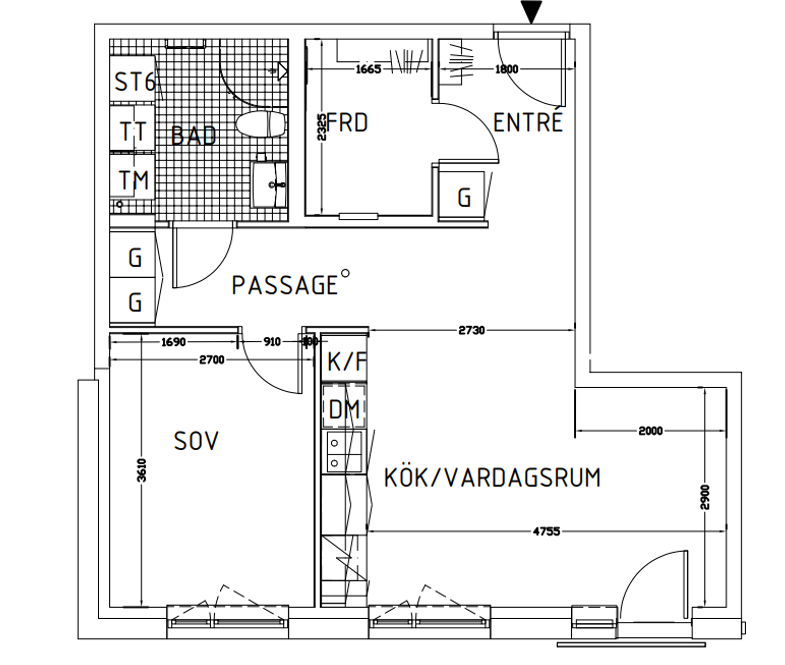

One downside to Sweden’s excellent tenancy protections is that they don’t like to bother the outgoing tenants during their notice period for photos or viewings. When I moved into my apartment on 1st September, the only visuals I had were a few photos of “similar” apartments, and a floorplan.

In truth, the floorplan is most valuable, since first-hand apartments are always unfurnished. Photos would only have shown me what other people had done with the space, but the floorplan allowed me to plan my own design.

And when I say “unfurnished” I really mean it. Apart from white goods (fridge/freezer, oven, washing machine, tumble dryer) there was nothing in the apartment. Not even curtains. Not even, as I discovered when returning home after dark on my first day, light fittings.

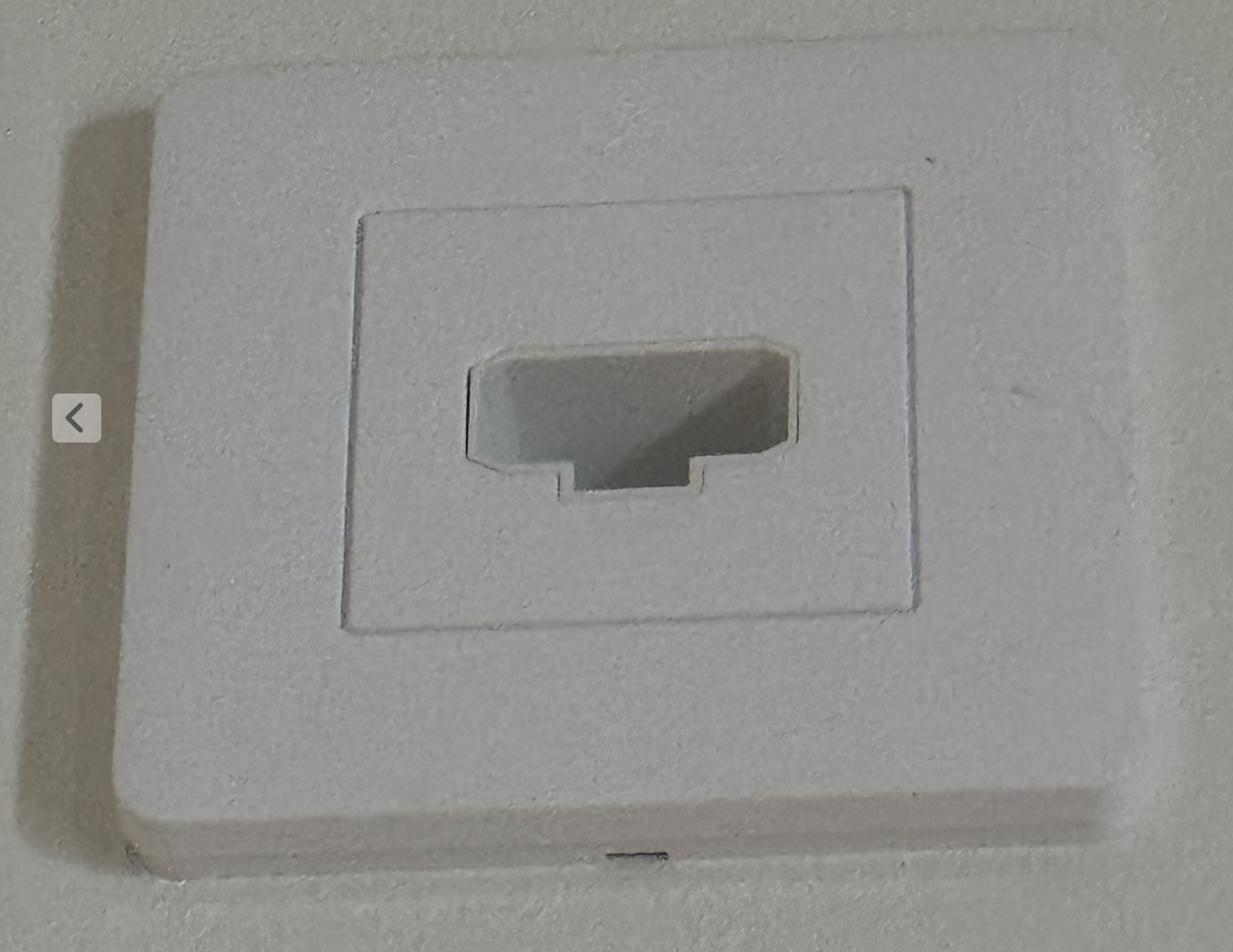

Instead of lights, dotted around the walls and ceilings of the apartment were these curious little sockets. I needed to buy light fittings, wire them to special plugs, and bring illumination to my home.

Tips

Yes, the official figures for housing queue times are horrifying, but I have demonstrated that it is possible to move straight into a first-hand rental in a major Swedish city.

- Join the housing queue early. It’s relatively inexpensive and, in the case of Malmö, does not require a Swedish personnummer. This means you can start accumulating points before you’ve even planned your move to Sweden.

- Be realistic. You are not going to be able to get a first-hand contract on a penthouse apartment in the most popular parts of Malmö, Stockholm or Göteborg. You will need to compromise on location. This doesn’t mean moving into a sketchy area with a high crime rate, but finding the newer developments on the edge of the city.

- Persevere. When you inevitably hit some famous Swedish bureaucracy (as I did with my income checks), stick with it. Explore every option, argue your point politely and don’t give up until all hope is lost.

- Budget for furnishings. Once you’ve secured that coveted first-hand contract, remember that you will walk into an empty, dark apartment. Make sure you’ve budgeted for all those trips to IKEA.